Even before he knew, a Calcutta newspaper published his article on its edit page. ‘I saw an article by one Bhaskar Roy, was that you?’ a college professor told him days later. After a month or so a little cheque landed in their letter box – for forty rupees. The year was 1978. That set the course for him. He never looked back, never wavered. Years later the question came back to confront him. After taking a master’s degree in English Literature from the University of Calcutta, he applied for a job as a newsman. A legendary editor heading the interview panel asked, ‘Why do you want to be a journalist?’ In 80s India, newspapers had taken over from the street fighters. The angry, angst-ridden generation took to writing the papers because their Revolution had failed. ‘That will be my response to the world around,’ he said.

During his years in journalism, he often went on high-risk assignments – to cover Hindu-Muslim riots in the dusty small towns of northern India, to interview Subhas Ghising, leader of the Gurkha uprising in the Darjeeling hills, to trace the genesis of Dalit politics in the underprivileged quarters of the city’s underbelly. In an article in India Today about the politically small but highly influential constituencies like the farmers, Muslim minorities and Dalits, he used the term ‘fringe leaders’ for the first time in the Indian context. In no time it became a catchphrase in political discourse. He at times gave a literary context to a political development to make it more appealing. Writing about Pandit Kamalapati Tripathi, an octogenarian Congress leader being bypassed by the party yuppies, he opened the piece with these moving lines from King Lear:

Pray, do not mock me.

I am a very foolish fond old man…

Almost twenty-five years and quite a few great publications later he left the mainstream media to edit The Equator Line, a themed quarterly magazine of new writing exploring long-form journalism in the Indian context. TEL emerged as a liberal platform at a time when Big Media had a lurch to the religious right. Serious, dignified, TEL takes a stand against majoritarianism, monocultural tendencies, patriarchy, xenophobia and jingoism.

Alongside his journalistic writing, Roy has successfully written fiction. The Defeat or Distant Drumbeats (Har-Anand, 1998), his first novel, earned the admiration of critics. ‘Roy writes well and will go far in the writing world,’ eminent writer Khushwant Singh said in his review of the book. It’s about the consequences of the government’s policy of caste-based reservations.

An Escape into Silence (New Century, 2000), his second novel, captures the intense emotions fuelling the Maoist uprising in West Bengal in the early 70s. The iconoclastic movement, destined to fail, was marked by the fiery idealism of twentysomethings and also insensate, brutal violence. Widely acclaimed, the book made a deep impact and still sells all over the world.

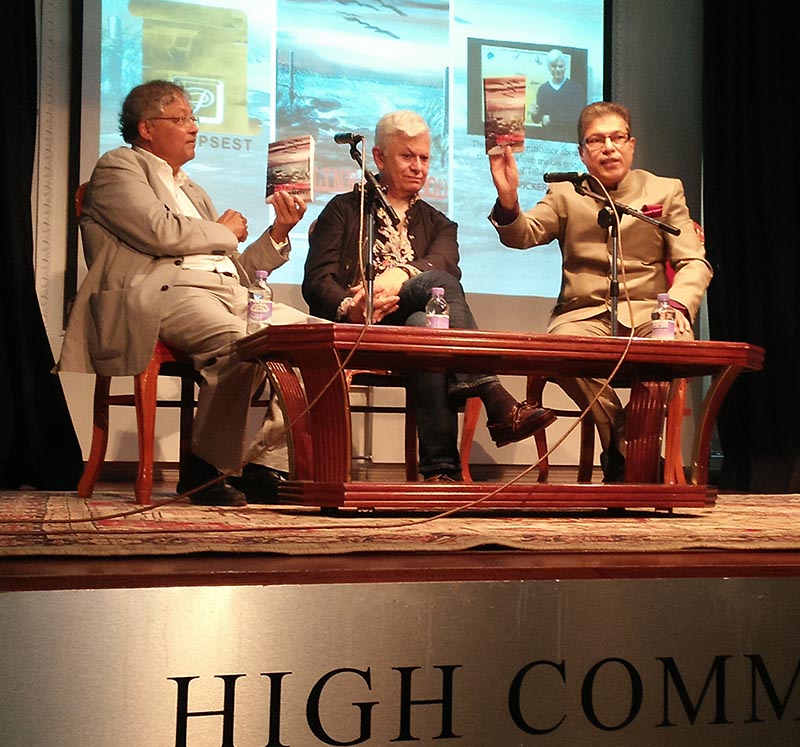

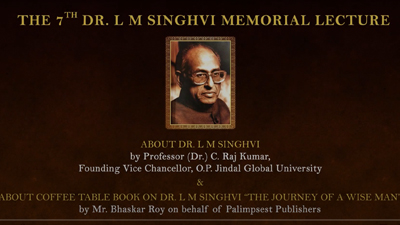

Roy’s deeply insightful essay, ‘Cricket’s Social Subtext’, forms part of the volume, India: A National Culture? (Sage, 2003). He also heads Palimpsest, his group’s publishing arm.

His wife, Dr Manimala Roy, is a well-known educationist and the author of From Shanties to School (Konark, 2019), a critically acclaimed work tracing deep linkages between India’s radical economic reforms of 1991 and migrant workers’ aspirations for their children’s education. Their daughter Protiti, educated at National Law School of India University, Bangalore, and Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, Tufts University, USA, is a policy lawyer working in Delhi.

Books

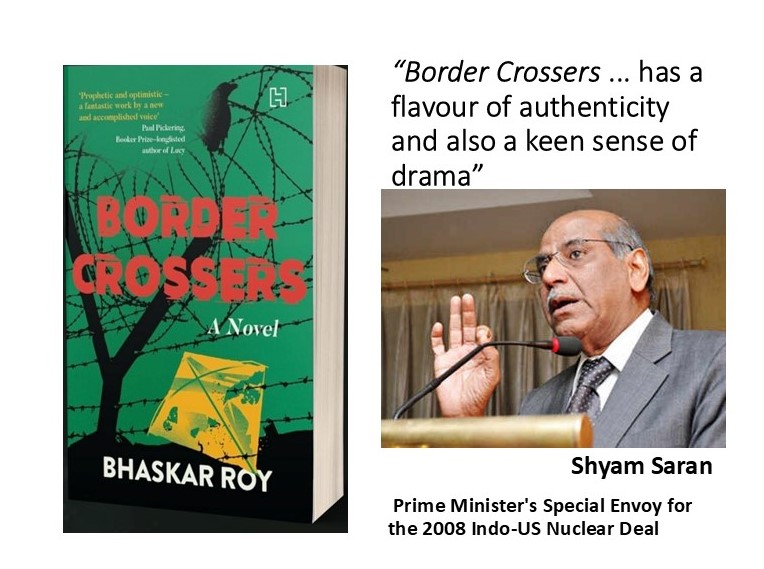

BORDER CROSSERS

Desperate for survival in the rude city, Rita is fortunate to get hired as a household help by a retired diplomat. At that moment, Arijit Basu does not know that she is an undocumented migrant. Convulsed by a marauding tide of events, the two are reduced to wrecks. Arijit’s fiancée, Nandita, fights bravely to recover the vulnerable girl from the circles of evil. The outcome of this struggle irrevocably impacts their lives.

Lyrical, epic and devastating, Border Crossers brings into sharp relief the many shades of terror and religious intolerance that shape the subcontinent.

Border Crossers reviews

Tehelka

https://tehelka.com/a-tale-of-displacement-love-loss-and-resilience-in-a-shifting-world/

The Print

https://theprint.in/india/border-crossers-of-migration-its-ramifications/2476036/

Outlook Magazine

https://www.outlookindia.com/books/book-excerpt-bhaskar-roys-border-crossers

https://www.outlookindia.com/books/finding-cultural-syncretism-in-bangladesh

Scroll

The Week

https://www.theweek.in/wire-updates/national/2024/09/01/lst2-book-borders.html

Millenium Post

https://www.millenniumpost.in/sundaypost/insight/survival-beyond-fractured-fences-591647

Wordsopedia

https://wordsopedia.com/border-crossers/

Storizen Magazine

https://www.instagram.com/storizenmag/p/DBgF308S31N/

Queen of Treasures

https://queenoftreasures.com/2024/09/13/border-crossers-by-bhaskar-roy-a-review/

Garhwal Post

https://garhwalpost.in/border-crossers-intersectionality-of-class-caste-gender-depicted/

Goodreads

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/217973700-border-crossers

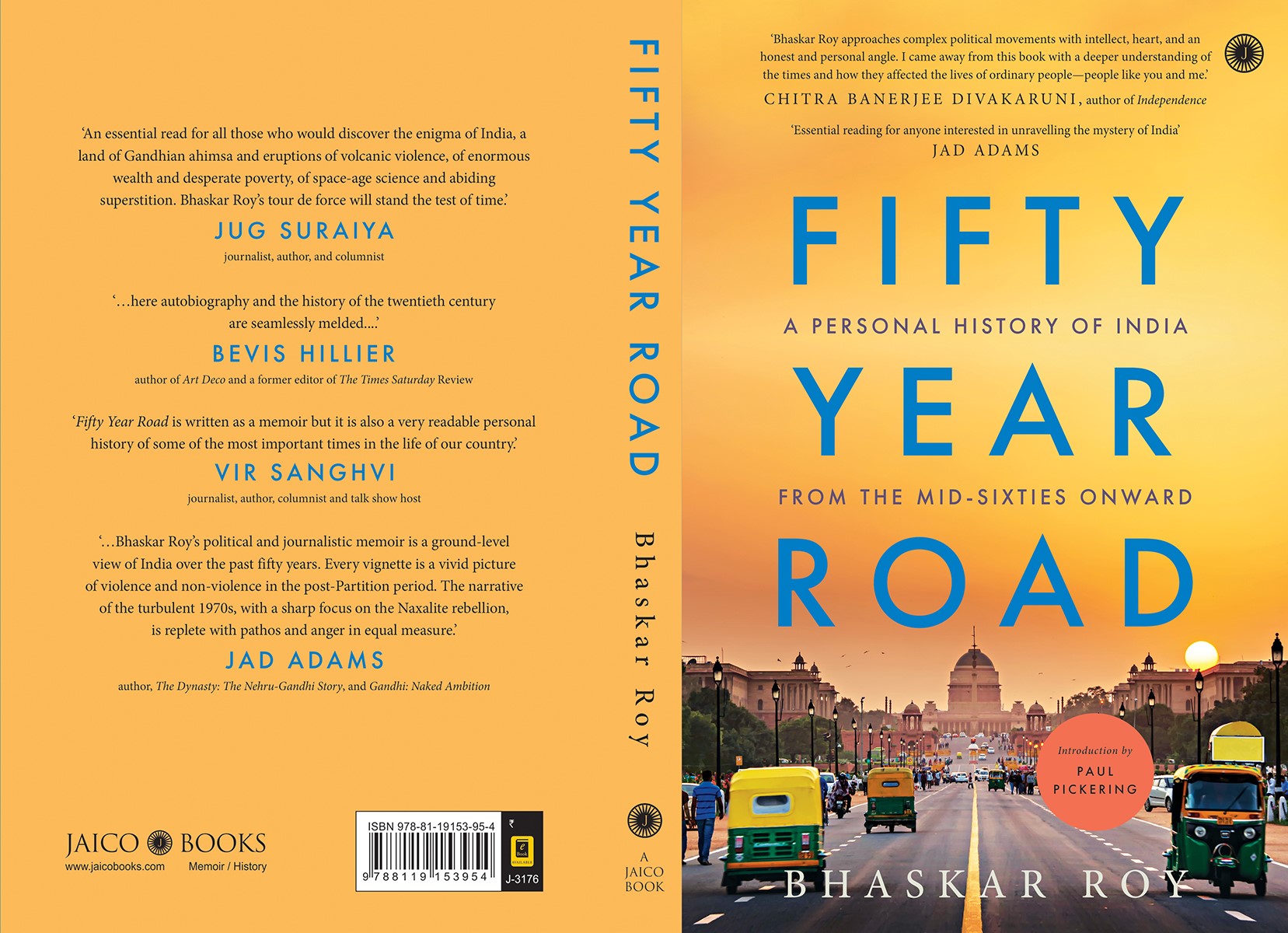

FIFTY YEAR ROAD

Bhaskar Roy’s Fifty Year Road: A Personal History of India from the Mid-Sixties Onwards is also a product of reflections and epiphanies made during the troubled lockdown phase. Mercifully, it doesn’t suffer from any pretensions. Instead, it mines a deeper vein of truth. Roy recognises that writing a memoir isn’t just an opportunity to chronicle the past for oneself, but also a means of reclaiming and reconstructing it for a broader audience.

The News on Sunday

In conversation with SETU, a popular North American media outlet

Fifty Year Road reviews

Outlook magazine

https://www.outlookindia.com/books/book-excerpt-charu-majumdar-and-the-naxalbari-uprising

The Tribune

The Week magazine

The Print

https://theprint.in/india/fifty-year-road-a-personal-history-of-india-mid-60s-onwards/1898866/

The Times of India

Scroll

Tehelka

https://tehelka.com/heres-how-autobiographies-ought-to-be-written/

Bound Magazine

Amar Ujala

Goodreads

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/204661148-fifty-year-road

Millenium Post

Bhaskar Roy approaches complex political movements with intellect, heart, and an honest and personal angle. I came away from this book with a deeper understanding of the times and how they affected the lives of ordinary people—people like you and me.

Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni

Essential reading for anyone interested in unravelling the mystery of India

Jad Adams

What Bhaskar Roy writes about in a brilliantly attractive and involving way is not just the end of colonialism but a tectonic shift in world power.

Paul Pickering

An essential read for all those who would discover the enigma of India, a land of Gandhian ahimsa and eruptions of volcanic violence…Bhaskar Roy’s tour de force will stand the test of time.

Jug Suraiya

Here autobiography and the history of the twentieth century are seamlessly melded…

Bevis Hillier

Fifty Year Road is written as a memoir but it is also a very readable personal history of some of the most important times in the life of our country.

Vir Sanghvi

THE DEFEAT OR DISTANT DRUMBEATS

One story leads to another. Ominous dark clouds gather in the sky as a prelude to disaster. The twilight hour disappears from the life of simple folk. From one story to another to many. They run parallel, clash and finally merge into each other. Do they really? Why should the ghosts then peer into god-fearing homes, fireballs roll over the moor and the one-legged one unleash terror from the haunted palace? But the veil of gloom, like thTHE DEFEAT OR DISTANT DRUMBEATSe spring festival before it, is not permanent.

Between stories space dissolves, time loses its meaning, borders fade away. One story contradicts the other and complements too. A child is born at the hour of self-immolations and breathes in the smell of blood and anger. One stream of politics, a way of life, comes to an end, a new campaign begins.

All this about a defeat? Maybe, maybe… but then… the drumbeats boom dismantling the tyranny of night, overcoming the accidents of ordinary life.

Khushwant Singh, The Hindustan Times

The first novel by journalist Bhaskar Roy could be described as a work in the genre of magic realism… Roy has done a commendable job. The pace is racy and the narrative never flags. Where Roy is really in his element is in the magical part. The narration of the adventures of Bhola and the Vanished Kingdom and the haunted house shows much promise.

S. S. Percy, The Hindu

AN ESCAPE INTO SILENCE

Despite the brisk breeze from the south and loud Hindi film songs on the radio, a gust of cold wind blows from the lost rivers of the land in an uneasy reminder of a sneaky winter. Marxist street- fighter Bachchu Sen returns to Barasat. Things begin to happen.

Unable to make sense of his situation, a sensitive young writer drifts dangerously into two conflicting worlds. What follows is a confrontation between a traditional tolerant society and ruthless politics of indoctrination, a secluded past and searing present.

In a significant way the story follows the love-loss-reconciliation trajectory of the old tales. That girl after all comes back to the young protagonist one wet, wispy winter afternoon. But where it daringly breaks free of conventions is in its attempt at building a parallel between the terrible happenings in the outside world and the troubled, tortured state of an adolescent mind.

An Escape into Silence is an impressive tour de force from a writer who combines good writing with psychological energy.

Dr Karan Singh

Bhaskar Roy’s novel is fascinating. This beautifully crafted literary creation makes history vivid and alive. Roy portrays Bappa – the central character – with great care.

Avijit Pathak, Mainstream

Bhaskar Roy’s novel offers a mature view of life and politics in Bengal, from the Naxalite movement through the years of the Emergency and beyond. Ostensibly about a young man’s coming of age in a confused political climate, it is in effect a portrayal of a disenchanted society that dares to hope in spite of individual and ideological betrayals.

The Little Magazine

An Escape into Silence has a deceptive quietude about its title and the opening chapters. But once you have entered the world of Bachchuda, the Marxist street fighter, you are swept by the surge of passion…

Malashri Lal, IIC Quarterly

Bhaskar Roy has displayed the grit to grapple with the most complicated period in Bengali life after Independence – the aftermath of the Naxalite Movement.

Biblio

Bhaskar Roy’s novel is shot through with piercing reminiscences of this [Naxalite] movement in a most poignant way… he has succeeded in a surrealistic retelling of the Manasa myth where Behula transports her dead husband on a raft, learning to look death in the face, teaching us to defy its stratagems.

Alokeranjan Dasgupta, Indian Literature

For An Escape into Silence he decided to intertwine an East Bengal legend with the political situation of the 1970’s. [In the legend] a newly married bride discovers that her husband has been bitten by a snake. He dies without their marriage being consummated and she travels down the river in the hope of his returning to life.

Interview in The Hindustan Times

The ambience of the period in which the story is set is one of fear and uncertainty. The aura of the Naxal movement provides a poignant addition. This is through the memorial plaques of some of its leaders. Bappa’s psyche is moulded when he gazes on the plaques of these leaders killed in encounters.

Srinivasan Subhramanian, The Telegraph

An Escape into Silence is an attempt to recreate the turbulent seventies when Bengal was rocked by the Naxalite movement, and when young men and women fought for what they believed were their ideals… Roy inserts to his credit, some observant details about the city, its steady creep into the outskirts, and its buzz of little magazines.

Uma Mahadevan-Dasgupta, The Book Review

As if to match the complexity of his narrative with the twists and turns in the life of the poet-protagonist, Bhaskar Roy constructs a taut, well-researched plot… The writer also weaves in an account of the dying rivers in the land that stretches from Calcutta to the border town of Bongaon along with myths and legends that local people keep alive through rituals.

Aruti Nayar, The Tribune

India: A National Culture?

The last two decades of the 20th century have witnessed a spectacular return of national consciousness. In this exciting and unique collection of essays, eminent academics, art historians, photographers and dancers focus on one essential ingredient of the making of Indian nationalism – i.e. the ingredient of culture, and one that has resurfaced in everyday experience. Their essays contribute incisive analytical comment on, and very different readings of, the fabric that constitutes ‘culture’.

From the early stirrings of national fervour in the second half of the 19th century, through the secularism of the Nehruvian era in the 1950s, to the all-pervasive and persuasive refashioning of culture to political purpose, the contributors demonstrate convincingly that culture is not a static entity. Rather, it can be refashioned, reinvented or co-opted to suit political purpose.

It is time, they argue, to once again reinvent an Indian culture that is intangible, that gets under the skin to resist the vicissitudes of political agendas.

Bhaskar Roy’s novel is fascinating. This beautifully crafted literary creation makes history vivid and alive. Roy portrays Bappa – the central character – with great care. His inner world, his pain, agony and deeper feelings touch the reader. As Bappa explores the world, the narrative acquires great power; it engages the reader. Amidst the smell of the local train, the pattern of living in a small town, group meetings and poetry sessions, life reveals its complexity.

With Bappa the reader too begins to experience the hollowness of what is otherwise being projected as an ‘anti-Establishment’ life-project. One sees the intolerance of the Marxist party machinery which, it was thought, would finally restore freedom and happiness!

As Bappa’s disillusionment with the party politics intensifies his loneliness, he recalls Mrittika, her poetry, her body, mind and soul. It is in Mrittika and Mrittika alone that he can find his salvation, and realize the ultimate victory of poetry over all sorts of regimentation, meanness and violence… One day she comes to Ashoknagar, and Bappa believes that the impossible has happened.

Bappa held her with both hands, as close to himself as possible. His face rested on her head. Overcoming the sweet smell from her hair, the faint perfume from the body, came the intoxicating fragrance of seeds, of elemental rain piercing the heart of earth around the shed. She did not resist…

Is it an escape into silence? Or is it the recovery of the language we have lost amidst the noise of the world?

Avijit Pathak, Mainstream

Bhaskar Roy’s novel offers a mature view of life and politics in Bengal, from the Naxalite movement through the years of the Emergency and beyond. Ostensibly about a young man’s coming of age in a confused political climate, it is in effect a portrayal of a disenchanted society that dares to hope in spite of individual and ideological betrayals. An Escape into Silence is a story of love, longing and living history. A young writer struggles to make sense of a world woven out of memory, history, legends, heartbreaks and the curious politics of opportunism and indoctrination…And it is clear that Roy’s long experience as a political journalist covering daily news has significantly enriched this engrossing novel.

The Little Magazine

An Escape into Silence has a deceptive quietude about its title and the opening chapters. But once you have entered the world of Bachchuda, the Marxist street fighter, you are swept by the surge of passion…The novel brings alive familiar sights and sounds. The class differences are real and yet melt compulsorily. Typically the boxwallah sahib and the indigent rickshaw puller are both affected by the disruptive violence of the times… An Escape into Silence looks at collective power systems and the smallness of individual will. Whether it is the Naxalite era or the Emergency, college elections or the neighbourhood ballot box, how much of our lives are ‘rigged’?

Malashri Lal, IIC Quarterly

Bhaskar Roy has displayed the grit to grapple with the most complicated period in Bengali life after Independence – the aftermath of the Naxalite Movement. The tyranny of the Emergency with its draconian laws is just over and there is hope anew. Rarely has one seen such a sincere evocation of the young Bengali milieu – tea, cigarettes, poetry, politics, college union elections, boy-meeting-girl and all that.”

Biblio

Roy tells an authentic tale. He draws us into a subtext about the Maoist movement that came to be known as the Naxalite revolution, taking its origin in the north Bengal village of Naxalbari on May 23, 1967. On that day as the police combed the area to arrest peasant leaders, one policeman was killed, and the movement of protest spread overnight like wildfire.

Bhaskar Roy’s novel is shot through with piercing reminiscences of this movement in a most poignant way. Instead of recounting directly the gruesome killings carried out in those days, the author turns to poetry which was the very heart-beat of this neo-romantic, though ill-timed, movement… he has succeeded in a surrealistic retelling of the Manasa myth where Behula transports her dead husband on a raft, learning to look death in the face, teaching us to defy its stratagems.

Here we are confronted with an archetypical ballad-cycle which emphasizes the fatedness of a folk, circumscribed by a rather stringent socio-religious system. And yet there prevails an uncompromising urge in its spokeswoman Behula, the ‘bride-widow’, who forces a way through the dark area of doom and destiny. Roy correlates this character to the women who lost their close relatives during the repressive Emergency.

“The woman in your poem reminded me of Behula, why I do not know. Like Behula she was ready to carry the burden of her ill-fated, short-lived love, and like her she was bold enough to talk about her own desire, her own passion… (pg. 120)

This twist in the given thematic continuity imparts to the novel a unique dimension. The reader is immediately reminded of Grusha’s Song for her Beloved in the Caucasian Chalk Circle by Bertolt Brecht.

Alokeranjan Dasgupta, Indian Literature

“I read this book on the Cultural Revolution written by an American and I was immediately reminded of the Naxalite movement in West Bengal during the seventies. It surprised me that how one person’s views and politics could affect one generation of people thousands of miles away,” says Roy, whose earlier book The Defeat or Distant Drumbeats was about Mandalisation.

For An Escape into Silence he decided to intertwine an East Bengal legend with the political situation of the 1970’s. The East Bengal legend has it that a newly married bride discovers that her husband has been bitten by a snake. He dies without their marriage being consummated and she travels down the river in the hope of his returning to life.

The story is about Bachchu Sen, a Marxist street-fighter who gets caught between a traditional tolerant society and ruthless politics of indoctrination, a secluded past and quite a disturbing present.

“It was an intensely human era, there was no hypocrisy in what they did. In fact, they gave up everything they had for their belief,” says Roy. He vaguely remembers the period he so extensively researched for the book.

“I know some people from that time, who were part of the Naxalite movement. It’s really sad to see them today. They are such a disillusioned lot, who can’t integrate themselves into the present society.”

A full-time journalist, Roy was not willing to compromise on the content.

“Most publishers I approached wanted something or the other changed. But I stuck to what I really wanted to write about,” he says.

Interview in The Hindustan Times

The ambience of the period in which the story is set is one of fear and uncertainty. The aura of the Naxal movement provides a poignant addition. This is through the memorial plaques of some of its leaders. Bappa’s psyche is moulded when he gazes on the plaques of these leaders killed in encounters.

Srinivasan Subhramanian, The Telegraph

An Escape into Silence is an attempt to recreate the turbulent seventies when Bengal was rocked by the Naxalite movement, and when young men and women fought for what they believed were their ideals… Roy inserts to his credit, some observant details about the city, its steady creep into the outskirts, and its buzz of little magazines.

Uma Mahadevan-Dasgupta, The Book Review

As if to match the complexity of his narrative with the twists and turns in the life of the poet-protagonist, Bhaskar Roy constructs a taut, well-researched plot… The writer also weaves in an account of the dying rivers in the land that stretches from Calcutta to the border town of Bongaon along with myths and legends that local people keep alive through rituals.

Aruti Nayar, The Tribune

India Today

31 October 1989

Mahendra Singh Tikait, Syed Shahabuddin, Kanshi Ram, representS powerful electoral triumvirate Kanshi Ram Leader, Bahujan Samaj Party with the genral elections round the corner, their shadows are looming large on the political horizon. Like vandals capable of wrecking the fortunes of the major contenders, a strange triumvirate – Kanshi Ram, Mahendra Singh Tikait and Syed Shahabuddin – has staked its claim to the electoral sweepstakes.

The trio have little in common except for the ability to cut into the votes of both the Congress(I) and the Janata Dal and upset the applecart of the principal bidders for power in the forthcoming elections. Though obscure figures a few years ago, the three are now weighing heavily on the psyche of leaders of the major parties.

Outlook

12 June 2020

Big Punch of the Little Magazine

RK Narayan’s Swami and Friends was published in 1935. And Raja Rao’s Kanthapura set a new trend in Indian fiction with its publication in 1947. If you recall the history of literary magazines nothing even remotely comparable comes to mind. Indeed, the effervescence of Indian writing in English has not spawned a literary magazine tradition of equal verve and elan.

Ravi Dayal, the iconic publisher who supported quite a few new writers, started Civil Lines in 1994. Though infrequent, the magazine left its impress on the audience with a new refinement. Unfortunately, it folded up after his death in 2006.

Madhu Jain, my colleague at India Today in the early 90s, started editing Indian Quarterly from Mumbai a couple of years before we launched The Equator Line in 2012. When we met at the India International Centre over lunch around that time, she talked about the mushrooming of think tanks as a possible story for IQ.

A hardcore newsman who had discovered Kanshi Ram and his Dalit politics in the slums of Regarpura in the backyard of Karol Bagh much before the world knew him, I could see the curious journey of print in the years ahead. A magazine analysing the trends in many areas of life and offering a perspective instead of ritualised news,

The News on Sunday

A Personal Window to the Past

Taha Kehar

A compelling effort to link an individual’s journey through time with that of his troubled surroundings

The pandemic-related lockdowns provided many of us with a doorway for contemplation. In those fraught moments of isolation, home-bound multitudes sought comfort in creative endeavours to prevent themselves from losing their spiritual equilibrium. It was, therefore, not uncommon to come across people who proudly asserted that they were working on their memoirs. A vast majority of these books are self-indulgent autobiographies that present vainglorious accounts of perceived valour.

Bhaskar Roy’s Fifty Year Road: A Personal History of India from the Mid-Sixties Onwards is also a product of reflections and epiphanies made during the troubled lockdown phase. Mercifully, it doesn’t suffer from any pretensions. Instead, it mines a deeper vein of truth. Roy recognises that writing a memoir isn’t just an opportunity to chronicle the past for oneself, but also a means of reclaiming and reconstructing it for a broader audience.

The Indian Express

19 June 1994

Atal Behari Vajpayee

Statesman in waiting

Even though he has grown up in the Sangh, the impress of Nehruvian liberalism on him is only too pronounced

The day after he made the controversial remark in the Lok Sabha bailing out Prime Minister PV Narasimha Rao from a difficult situation, Atal Behari Vajpayee shared the platform with the extreme-right phalanx of the Hindutva proponents at a book-release function. In the same row were sitting RSS Sarsanghachalak Rajendra Singh, BJP president LK Advani and former party president Murli Manohar Joshi.

As the audience for the launch of BJP MP Vijay Kumar Malhotra’s book Lotus was mainly drawn from the Sangh Parivar, the tension was palpable. An invisible line seemed to separate Vajpayee from the others. However, the moment he took the mike the mood changed.

The Week

21 June 2020

Literary magazines in India and their short lives!

By Zafri Mudasser Nofil

New Delhi, Jun 21 (PTI) Meant to be off the beaten track, literary magazines in India have been showing signs of struggle over the years in finding a meaningful audience for the high-quality writing and, barring a few, dying a silent death.

According to Tabish Khair, who has authored various books, including poetry collections, Indians hardly subscribe to literary magazines.

“Literary magazines have high mortality all over the world, though there are some that sometimes make it to 100 years or more. In India, their lifespan is shorter because India has hardly any literary readership,” he told PTI.

The Gaya-born Khair, who now mostly lives in a village off the Danish town of Aarhus, has been writer in residence at Canada’s York University, and visiting fellow or guest professor at Cambridge University and Leeds University in the UK.

Senior journalist Bhaskar Roy, however, has the credit of single-handedly reviving the literary magazine tradition in India with his successful stewardship of “The Equator Line”.

The themed quarterly magazine of new writing that has evoked positive response from the literati since it first hit the stands in late 2012, is now regarded as a lively liberal platform for young voices in subcontinental writing

.

Outlook magazine

17 December 2023

A REQUIEM FOR A DREAM

By Bhaskar Roy

The slice of sky I could see through the branches of the robust silk-cotton tree outside my cabin was being crisscrossed by relentless fighter jets that foggy February morning. The day before, Indian bombers pounded the Balakot terror-training camps to retaliate the Pulwama killings. Looking at the quaint shopping courtyard below, I wondered which payloads the fierce aircraft were carrying—Indian or Pakistani? From my office in the rundown urban village of Shahpur Jat—though technically very posh-sounding Panchsheel Park—I looked at the working-class people on their daily drudge. Do they care less about bombs from the sky?

.

The Times of India

20 February 2011

Lord of the rings: Why aam aadmi is sitting pretty

Nasir belongs to a village in Bihar but has moved some distance from his physical and mental origins — he works in an office canteen and recently, had to contact a mobile phone helpline. He says he was gobsmacked when a polite female voice answered the phone and all his queries. “I never thought they would bother to talk to me,” says Nasir.

Clearly, the canteen boy had underestimated his importance as a mobile phone subscriber. Across India, there are many like him and they are part of a radical change in mindset, expectations, worldview and aspiration. But the revolution underway is not the result of a political doctrine — it is the product of new technology.

Outlook

13 September 2021

Author Paul Pickering’s Elephant: Felt With A Trunk

Contemporary English fiction is largely concerned with cosmopolitan life, focusing on new realities like sexual diversity, man’s relations with technology and responses to myriad social changes. The outcome is often outstanding—Ian McEwan’s Saturday and A Machine Like Me, or Bernardine Evaristo’s Girl, Woman, Other. Yet such stories rarely cross the city limits.

Elephant, Paul Pickering’s new novel, is an irreverent attempt to reverse this municipal centrality by harking back to the robust picaresque tradition of the 18th century. Pickering’s own journeys seem to have brought him closer to the genre inhabited by masters like Defoe and Fielding. As a young man he joined the Sandinista revolution as an internationalista and listened to Fidel Castro’s nine-hour harangue, capping it with a bone-crushing handshake with his hero at a sugar mill during the victory celebrations. In Perfect English he recounts this experience. The Leopard’s Wife traces his travels through the Congo. While researching Over the Rainbow in Afghanistan, he narrowly escaped a Taliban attack. The pull of the picaresque, like the call of the road, seems to have been irresistible for Pickering.

He has lent scale and grandeur to the simple story of an orphaned boy’s relationship with an African elephant—a throwback to Mowgli and Hathi in Kipling’s Jungle Book—to turn it into a fascinating epic spanning civilisations, continents and centuries.

Outlook magazine

13 July 2025

A Good Read On A Long Flight

By Bhaskar Roy

Off to Boston, for the long flight, I took two books—Pakistani-British writer Kamila Shamsie’s Kartography was one of them. There is a backstory to it

A new publisher looking for good scripts, I landed in Wajahat Habibullah’s office one day. Chairman of the National Commission for Minorities, he had worked with both Prime Ministers Indira and Rajiv Gandhi. The trait of mutual trust had actually run across generations.

On the wall behind his bureaucratic leather chair was a black-and-white photograph: Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and an equally handsome man riding their horses in a bucolic locale. ‘My father,’ Wajahat quietly said, noticing my curiosity.

.

India International Centre Quarterly

Vol. 29, No. 3/4, India: A National Culture? (WINTER 2002-SPRING 2003), pp. 252-258 (7 pages)

Cricket’s Social Subtext

One inspiring image in the backdrop of insensate communal violence in Gujarat that stayed with the television viewers in 2002 was India’s main strike bowler Zaheer Khan’s bristling burst of pace targeting an opposition batsman. Young Zaheer, who has already established himself as the team’s most dependable speedster by virtue of his sheer pace and penetration, happens to be from Baroda, an important city and cultural landmark of the afflicted state.

At a time when the gloomy landscape of strife made even the most incurable optimist wonder about the future of Indian pluralism, the beaming face of the new cricket star after hunting down yet another victim in the willow war, comes across as a reassuring symbol of hope. The red ball in hand, the left-arm bowler striding down the run-up in an upfront movement acquired an iconic dimension.

Outlook

09 August 2021

Jhumpa Lahiri’s parents had migrated from India first to Britain, and then to America, and she grew up in Rhode Island in the 1970s. The initial struggle of a migrant’s life may have bruised her parents’ experiences, but only inspired Lahiri’s stories. Her literary fame began with the runaway success of her debut short story collection Interpreter of Maladies that won the Pulitzer Prize, and grew with her subsequent books. In a surprise move, she left with her family for Italy in 2012 to write in Italian, to explore a new culture, and more importantly, to reinvent herself, migration being her inheritance. Once on the road, journeys become a way of life. Her father, a university librarian, was a constant reminder of life left behind. And her mother, usually dressed in a sari, gave the daughter an idea of home thousands of miles away in India. Between the two generations, this was the third stretch of migration, but very different from the earlier two.

The woman protagonist of Whereabouts, a university teacher in an unnamed city in Italy, despite sharing many traits of the characters in Lahiri’s previous books, is a very different person. Full of self-assurance, the city her home, this single woman,

Outlook

21 September 2025

Home And The World

By Bhaskar Roy

One night in late November I cross the under-repair bridge on a nameless river—might be an ingress of the Arabian Sea—inhaling hyacinth-layered dark water on my way to Poornathrayeesa Temple to breathe in the verve of the annual festival. Seven caparisoned elephants in a row mildly swing their trunks to the tune of the large resonant bell and beats of the chenda drum. Burnt ghee from the glowing diyas hangs thick in the air around. In an upstairs hall, lavishly painted Kathakali performers are waiting for the classical singer to end his recital. The god here definitely has a baroque grandeur, a flair for extravagance. And as if to lend colour to the deity’s majesty, well-turned-out boys and girls look for lonely corners to get lost in closer moments.

TEL 15: Liminality of Faith

April-June 2016

THE FAITHSONG

When the Venetian merchant Marco Polo travelled across what is now the Middle East on his way to India and China in the late 13th century, it was an exciting place, a melting pot of ideas, influences and an amazing space where faiths intermingled. The intrepid traveller with an eye for the unusual, came across Jews, Christians, Muslims, Persians, Turks, Mongols, Buddhists and others. Though the Crusade had already been fought, cultures were still feeling each other out and imbibing each other’s influences and assimilating. The degree of sharing and coexistence was indeed remarkable. According to Rabbi Benjamin of Tudela, another traveller of that time, the city of Baghdad, the capital of the Muslim Abbasid Caliphate, had 28 synagogues. Jews in Azerbaijan lived in complete harmony with Turks and others. In his Travels, Polo wrote about Nestorian Christians, Muslims and „idolaters‟ living peacefully together.

The Times of India

7 February 2007

A Session with Bishop Desmond Tutu

Archbishop Desmond Tutu is a voice of sanity in an increasingly violent world. While in New Delhi to participate in the centenary cele-brations of Mahatma Gandhi’s satyagraha in South Africa, the anti-apartheid activist and Nobel laureate spoke to Bhaskar Roy:

Is it possible to follow Mahatma Gandhi in a world which is increasingly becoming both intolerant and intemperate?

The most important point to make about his relevance is the assertion that we live in a moral universe. The fact of the matter is that the perpetrators of evil almost invariably end up biting the dust. When you look at history you realise this.

It may take a long time but it happens. Ultimately truth, goodness and justice prevail. That’s a very important assertion that Gandhi’s philosophy teaches us. What we have learnt from him is that in a conflict we ought not deny humanity to the enemy.

His instinctive acceptance of common humanity teaches us not to dehumanise the other man. We really cannot demonise our adversaries. We need to acknowledge this in the context of our times.

In the 20th century evil was largely represented by the state. If you look at this century, you see that evil is often a non-state player.

Bhaskar Roy as Publisher

Bhaskar Roy is one of the finest editors around. A manuscript, often a little raw and clumsy, is edited to its fullest possibility by him. With his keen literary sense and thorough knowledge of contemporary history he often brings out an interesting part that the author unknowingly underplayed. Truly, a book is reborn in his hands.

A development professional attempting his first book, I submitted my manuscript to Bhaskar Roy. When it came back edited, I was amazed. It was very much my own writing, not a single fact altered, the soul remaining intact but it read very different. It had a smooth flow I had not anticipated. In his own quiet way Roy did wonders. He is more than an editor. Beginners like me had a lot to learn from him. Such an editor is difficult to come across.

For a new writer it’s very reassuring to have someone like Bhaskar Roy as your editor. Indeed, I learned a lot about writing from him.

Media

Contact

Email: roybhaskarwrites@gmail.com